Yom Kippur 5782

As many of you know, I turned 61 a few days ago, having one of those Virgo birthdays that always falls inconveniently close to or within the High Holy Days. At my age and for some time now birthdays have become a natural moment to seriously reflect on one’s mortality. All the moreso if one’s birthday treat is a trip to the ER with a kidney stone, in terrible pain that I remember the fact of but, barukh Hashem, have forgotten the feel of.

On these late- and now post-middle-aged birthdays of mine, I inevitably take stock of who is still around and what it might mean if I weren’t. The stocktaking was very present this year. My husband and I just a month ago lost one of our best and oldest friends, half a year younger than me, taken in four months by a disease rare and pitiless. We held a memorial for him right here at Ner Shalom. The next day I made a pastoral call on someone who is 100 years old, and their only wish was to leave this world behind, but that ability continues to elude them.

And so the stock-taking. Hodieni Yah kitzi. How long will my life be? Will it be not enough? Will it be too much? Can I even imagine such a thing?

In my defense, ruminating on death is more than just a Jewish neurotic tendency. It is normative Jewish practice – in fact, it is an explicit theme of these High Holy Days and of Yom Kippur in particular. We stand before the open ark and ask, “Who will live and who will die?” Because we’re all asking it anyway. So why not ask it together, in ritual petition and protest, baring our frightened souls to the Divine?

Yom Kippur is designed to be a meditation on death, an imitation of death. We don’t eat, we don’t drink, we don’t work. We don’t adorn ourselves, have sex, or look to entertainment. We wear white clothing as if to represent shrouds. By the end of Yom Kippur, if we are lucky, we have transcended the limits of our physicality and we are translucent, hovering between the worlds.

But why? Why a communal ritual in which we rehearse our own deaths? For Yom Kippur it is strategic: Yom Kippur wants us to feel the tick-tock of time and the uncertainty of the future so that we make good now. Heal relationships. Make sure we’re in a good place with our loved ones and our communities and the Ineffable, for that matter. Yom Kippur wants us to notice the loose ends. The damage we’ve inflicted and haven’t yet cleaned up. Imagining our deaths creates the needed urgency: make good, make things right, forgive, ask forgiveness – now. There is no time to waste because any day could be the day.

In my thinking over these last months about the coming shmitah year, the fallow year, that we are now at last entering, I have become convinced that shmitah is also a memento mori, a reminder of death. Shmitah, which means “letting go” or “relinquishment” in Hebrew, asks us, by letting the land rest without our tinkering, to imagine how the world might be, how it might go, without us in it.

Because what is death if not the greatest relinquishment of all? The moment when we let go of all our investments and obsessions, preoccupations and pursuits, our hard-earned wisdom and our proudest accomplishments. Our failures and our stuckness in them. At death we relinquish all of it. At shmitah time, we rehearse that relinquishment, letting go of our need to control what the field does. Not just the land, but the field of our endeavors – professional, personal, interpersonal. Imagining that field beyond our ability to cultivate or control it.

This imagining is hard to do. We hang on tightly to our striving. Our activities and ambitions are a key source of our identity. Who am I? I’m a rabbi. I’m a negligibly famous drag queen. I’m a parent. Some of that stuff really does hover around the “who am I” question and some of it is just resume, not who I am but what I do.

Shmitah, by suggesting a kind of receding from the parts of our lives that are enterprise, affords us an opportunity to look more deeply and kindly at who we are underneath. When I strip away the resume, when I strip away my story about myself, as would be stripped from me upon my death, what is left? Who am I? What is this neshomeh, the me that is underneath and beyond all of that biographical stuff?

So hard to imagine. We are so tied to our conditions and our strivings. Sometimes it is as if it is the striving that actually keeps us going. The obligations and assignments and vices and ambitions. We strive because if we stop, so will life.

In Moonstruck, one of my favorite movies, Rose Castorini, played by Olympia Dukakis, realizes her husband is having an affair. She is trying to puzzle out why. She asks her daughter’s fiancé why men chase women. He answers, “Maybe because they’re afraid of death.” Just at that moment her husband walks in. “Cosmo,” she says, “I just want you to know that no matter what you do, you’re still gonna die.”

Shmitah reminds us of the same thing. Whatever we do, no matter how hard we till those fields, we will all die. The field will move beyond our reach.

So we might ask “who am I,” without all the things I’m chasing, even if those are laudable things – learning and justice and a better world. What is the “I” that is deeper or higher, more fundamental, more connected to the Source than what I usually think of as me? I want to know because that deeper me might be a little less needy, a little more accepting, a little more loving, than the me that is so invested in how things ought to go, the me who is easily irritated or disappointed in others or myself. What is the me that is beyond the touch of human ambition and judgment? The me that is a field at rest, only sprouting what grows naturally?

Beyond the prohibition on cultivation, the shmitah laws provide another key practice: Deuteronomy 15:1-2 says:

מִקֵּ֥ץ שֶֽׁבַע־שָׁנִ֖ים תַּעֲשֶׂ֥ה שְׁמִטָּֽה׃

וְזֶה֮ דְּבַ֣ר הַשְּׁמִטָּה ֒ שָׁמ֗וֹט כׇּל־בַּ֙עַל֙ מַשֵּׁ֣ה יָד֔וֹ אֲשֶׁ֥ר יַשֶּׁ֖ה בְּרֵעֵ֑הוּ

“Every seventh year you shall practice a shmitah – a relinquishment, a release. And it shall go like this: every creditor shall release the debt of their fellow . . .”

Somehow shmitah consciousness in Torah incorporates both fallow fields and the forgiving of debts. What connects these these two practices? On a societal level they share a value of resetting the economy, letting human enterprise revert to a more basic state of less control over and more equality with. We are not over the Earth any more than we are above the people who borrow money from us, the people who have been disadvantaged by the economic system.

But another connective tissue is that the release of debts is also a kind of re-enactment – or pre-enactment – of death. “You can’t take it with you,” goes the old saw. When you die, you relinquish all that is owed to you. Maybe in our legal world your heirs have a right to it, but for you it’s gone.

And so, shmitah suggests, why not experience in the present what it would be like to not take it with you? A debt is, after all, a 2-way obligation. I might owe you money, but you are yoked to me and to the debt, to remembering it, collecting it, clocking its repayment, worrying about its default. You are yoked to being my creditor, which creates a hierarchy that can interfere with our ability to just be fellow humans together. What would it feel like to have a good reason to let the debt go? To let it morph from obligation to gift? A loss on the books, but maybe a release for your heart.

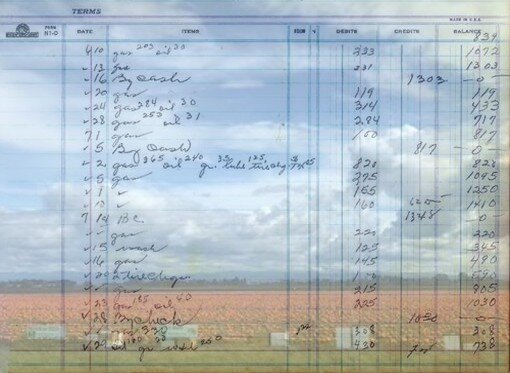

And all of that said, most of us here are not creditors. But there are other kinds of debts. Things that we feel others owe us, that we are still trying to collect on. Aren’t all our grudges in fact some kind of debt we feel we are owed? Some apology we are owed? This Holy Day asks us to forgive. But shmitah asks it of us in a different way. When you die, Cosmo, you will not be able to get satisfaction on any of the spiritual, moral, social debts on your ledger sheet. You will not, in death, get the apology that you have been waiting for in life. So why carry it to your grave? Why not imitate the grave now and release the debt? What would it feel like to let go of the apology you think you are owed? What a relief that might be not for them, but for you.

My friend Ric, by the time the trajectory of his disease was evident, had very little time to let go. He was forced to relinquish everything – the work he loved and believed in. The house he built and puttered in. But also his worries for his loved ones. The grudges and annoyances he surely harbored. At the end, we in his circle were all filled with shock and pain, but he had achieved a peacefulness that comes with letting go of everything.

What if we could achieve some fraction of that peacefulness in our lives by letting go without death’s hand forcing it?

Ultimately death is a kind of return. A return to a simpler state. To what we were before, whether that is pure spirit or pure earth.

After seven cycles of shmitah, in the fiftieth year, a jubilee year is proclaimed, a time of much relinquishment and much returning. Over and over the Book of Deuteronomy uses the verb shuv – from which we get our teshuvah word – to describe what happens in this climax of the shmitah process:

בִּשְׁנַ֥ת הַיּוֹבֵ֖ל הַזֹּ֑את תָשֻׁ֕בוּ אִ֖ישׁ אֶל־אֲחֻזָּתוֹ:

“In the jubilee year, each of you shall return to your holding,” i.e. to your ancestral land.

How close is this formulation to what we say about the human condition itself in Psalm 146. Do not trust in the salvation of other humans, it goes, because:

תֵּצֵ֣א ר֭וּחוֹ יָשֻׁ֣ב לְאַדְמָת֑וֹ בַּיּ֥וֹם הַ֝ה֗וּא אָבְד֥וּ עֶשְׁתֹּנֹתָֽיו׃

Because “Their breath departs; they return to their earth;

on that day their enterprises come to nothing.”

Letting go is what comes with returning. Letting go of our investments, our enterprises, the debts that are owed us. We let go of whatever control was not illusory to begin with.

On the 50th year, the shofar is sounded and freedom is proclaimed. Freedom from indentures, from complex land conveyances, from red tape. But there is more than that. Shmitah offers us a glimpse of freedom. When we let go, when we relinquish, we free ourselves.

And we free up space. Space for whatever arises. Which will undoubtedly be wild and beautiful and possibly unexpected. Or not unexpected; familiar! – because the seeds that grow at last will be the seeds you knew were there, native to the landscape, drought resistant, which your years of busy cultivation of Kentucky blue grass and topiary prevented from germinating.

Maybe it will be space for breath. Or rest. Or love. Or maybe the space will just be space. Min hametzar, we sang earlier, from the narrow, pressured place I called out. Anani vamerchav-Yah, and I was answered with space, the expansiveness of Yah, of what simply is.

We have called out from the narrow place. Ready to pry open our clenched fists and let go of some of what we hold onto so tightly. We can’t take it with us, so why bear its weight even a minute longer?

May letting go give us freedom. May beautiful wild things grow in our fallow fields. May we release the debts that keep us shackled. And may the gentle imagining of death bring transformation and preciousness to our one wild and precious life.

To read the Rosh Hashanah drash, “Happy Camper: Entering a Year of Letting Go,” click here.