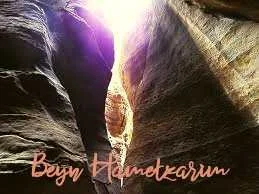

Welcome to the narrows. To the straits, as it were. Thursday was the 17th day of Tammuz, the day that marks the breach of the walls of Jerusalem by the Babylonians. And in three weeks is Tisha B’Av, marking the destruction of the Temple. We call these three weeks the Beyn Hametzarim – the in-between, the narrow days. A passage of constriction we must pass through.

We might remember that the Hebrew name for Egypt is Mitzrayim, a word related to metzar, metzarim. We interpret the word Mitzrayim which we also interpret to be The Narrow Place. Which suits the map of Egypt, since all of its population lives in a narrow corridor along the fertile Nile River.

But it’s not just geographical. Our symbolic memory of mythic Egypt is that it is a place of narrowness and constraints. We were enslaved there; our actions were limited; our breath impaired. Our mystics say that we were robbed of speech in Egypt. We had lost the power to speak for ourselves. When Moses was approached by God at the Burning Bush to be recruited for the Great Mission, his response was, “Who am I to do this? My tongue is heavy.” Our tradition suggests that speech returned to us only after leaving Mitzrayim and reaching Mt. Sinai, in the open spaces of the wide Wilderness.

Because of this rich symbolic history, we prize expansiveness. We pray for the wide-open expanse, like in the psalm we just sang. Min hametzar karati Yah; anani vamerchav-Yah. “From the narrow place I called out ‘Yah’ and the Divine answered me from the expanse of Yah,” from the merchav-Yah. Almost as if saying Yah is in itself is the breath that creates the expanse. As if all that time in Egypt or all the time we are troubled and focusing inward, we are just waiting to exhale. Calling out Yah gives us that chance.

But at the Taproot retreat I staffed two weeks ago in New Mexico, one of the members of the cohort challenged our preferencing of expansiveness. They said, “There’s value in the narrow place too. Important things can happen there too.” And that got me thinking.

Thinking about how often I want to retreat to a cozy and private place. How much my out-in-the-worldness needs to be balanced by time behind protective walls. Out in the expansiveness I can celebrate the far reaches of Creation; but then in my narrow space I can heal and repair and find the intimacy of Creation. In the narrow place there is gestation. In the narrow place there is embrace. Sometimes, when we bleed, direct pressure is the best course.

During these three weeks stretching from yesterday through Tisha b’Av, it is said that our access to the divine is somehow geared down. As if the Divinity reaches us through a stepdown transformer. The Chasidim say that instead of perceiving the Divine fullness as represented by the Divine name, YHWH, we instead get it as TDHD, which is YHWH with the value of one subtracted from each letter of the Divine name. So instead of Yahweh, we experience Tadhad. We see God through this veil; we experience the Divine stepped down.

But I wonder if that’s an unfair characterization; if it’s unfair to consider that a bad thing. I, frankly, never perceive God with clarity. I only ever perceive God through a veil of one sort or another. And sometimes a conversation is easier through a veil, or a curtain, or a mask. Or a lattice, like in Song of Songs. Or through a chink in the wall like in the story of Pyramus and Thisbe. Sometimes it’s easier to be honest, to open your heart, when you’re not looking the other smack in the face.

So I might ask us all tonight and maybe over these next three weeks, to notice what are the ways in which the Narrow Place can be healing and nurturing. What is the work that has to be done in the Narrow Place before we can then pendulum back to the Great Expanse?

Min hametzar karati-Yah. I call out to God from the narrow place. And Yah, when I do, you don’t have to pull me out of it. Just answer me, and be with me, right here.