Yom Kippur 5783.

There are things in this world so old, so elemental, that it is as if they always existed. So ancient and important that our ancestors struggled to figure out how they came into being. These are phenomena that figure in our stories and our Jewish lives, but are not specifically mentioned in our six days of Creation. Therefore, thought the sages, they must have already been here before God turned to say, “Let there be light.”

According to Talmud, these items include the Throne of Glory, the manna that fell in the wilderness, hellfire, the Messiah’s name, the design of the Temple, the Garden of Eden, and: teshuvah. [BT Pesachim 54a, citing Psalm 90:2-3 as prooftext.]

Teshuvah, that literally means “return” but implies “repentance” or “atonement.” Teshuvah, which is in part a practice and in part a longing and in part, hopefully, a native human capacity.

Teshuvah, that we talk about every year during this season. I would say that yes, it is “old as the hills,” but no – Talmud specifically says it existed before the mountains were raised. It’s as old as the Deep Water and the Primordial Darkness.

What does it mean to say that teshuvah existed before Creation itself? Maybe it is so that we feel that teshuvah is always there for us and always has been, even when we think all is lost and there is no repair that can be done. It is elemental and primordial and there for us like oxygen. Or maybe it means that it is hardwired into us alongside our very free will. Because free will means that we will make mistakes and we will cause harm and there has to be a road back, a return. Teshuvah was created in anticipation of our being free beings, to offer us the eternal possibility of change.

Our High Holy Day theme this year is about tending the sacred. Teshuvah is a sacred practice, even though it is always difficult, sometimes painful, not always satisfying. It’s easier if it is done in the immediate wake of an injury. It’s easier if it’s practiced regularly – not just on Yom Kippur but as the tough things happen. Teshuvah is a practice of humility, as the prophet Micah says, hatznea lekhet im Eloheykha. “Walk humbly with your God.” [Micah 6:8.] The path of teshuvah is a path of humility. And that path is easily overgrown.

My own path of humility is often entirely obscured by the hibiscus and the gardenias and the other gaudy blossoms of my ego. You have to walk the path of teshuvah, the path of humility, regularly, in order to keep it clear enough to use.

My desire to do teshuvah is often outweighed by my fear of doing teshuvah. My fear of opening my eyes to what I’ve done wrong. I see the harms I have caused and they look to me much like sleeping dogs and I imagine that there is wisdom in letting them lie, despite a lifetime of experience telling me that they will bite one way or the other.

I aspire to teshuvah, and frequently fail.

But teshuvah is as Jewish a practice – and as everyday a practice as washing hands and making blessing over food. Teshuvah is old magic; scary-seeming but almost always conjuring into existence something better than the situation we’re in.

Tonight I’d like to look at the possibility of collective tesvhuvah. Where we, as a community or a collectivity or a nation, take stock of harms we have caused, or the harms we didn’t oppose, or the harms we benefited from.

Teshuvah of a collective nature has always been available to us, even though we don’t spend a lot of time thinking about what it might look like. On Yom Kippur afternoon we always read the story of Jonah, and we tend to focus on Jonah, the individual, the reluctant prophet. What’s up with Jonah, we wonder. But what flies right by in that story is the fact that when Jonah ultimately goes to the people of Nineveh and confronts them with their deeds and God’s judgment, they do teshuvah – all of them; the whole country fasts; the king descends his throne and sits in the ashes. Just imagine that in America.

We are not told what the sins of the people of Nineveh were. But we are left with an image of a nation willing to take a hard look at itself, in a way that ultimately saves them from themselves.

There is an invitation for collective teshuvah in front of us at this moment of history, being proffered by too many modern-day prophets to count, and by too many to ignore. It is taking the form of the movement for reparations, both to the descendants of enslaved black Americans and to the descendants of the indigenous people of this continent. The movement for reparations is still controversial but, I think, is a critical piece of teshuvah. It is an invitation for the collective to develop its moral conscience, to look at how old harms continue to live with us until they are addressed, to notice how we are implicated even in histories we didn’t actively participate in.

As American Jews, particularly those of us who are of the white-assimilated Ashkenazi ilk, we have a longstanding story that we tell about coming from nothing, refugees from anti-semitic violence, with only what we could carry on our backs. And from this humble beginning we made good.

It is a good story, and it is true. But it is not complete. We made good in a country that was built on stolen land, by the stolen labor of stolen human beings. The ground was prepared for us to succeed far beyond the ability of black descendants of enslaved people, who were denied anything like equality, at just about every turn of American history.

Here’s a little of that history, and I’m sorry, for many of you I know this is review. But there are pieces that are new even to me, so I want to share some of it.

After Emancipation, at the beginning of Reconstruction, there was some popular vision of what a post-slavery United States might look like. Political enfranchisement, economic opportunity. The famous promise of forty acres and mule made to former slaves – that is, actual holdings and a path to independence, advancement, prosperity. This promise collapsed after a dozen years, under political pressure to compensate and restore the wealth of the white south, rather than compensating the people whose unconsenting and unpaid labor had built that south. Forty acres and a mule became sharecropping, designed to do the opposite – to keep formerly enslaved people living at subsistence level.

The years after Reconstruction saw the rise of government-sanctioned terror, the KKK, thousands of lynchings. Over time we got Jim Crow laws and segregation. And while we think about these as primarily southern phenomena, the entire country had benefited from the wealth of the south. And many of the continuing means of suppression were national in scope. In the lifetimes of many in this room, we saw the GI Bill, which made it possible for our white fathers or grandfathers coming home from the war to buy their starter house, which we then inherited at much greater value. For the most part, the 1.2 million black veterans returning from the War were prevented from enjoying any of the bill’s benefits; through redlining and refusal to sell homes to blacks; the violent terrorizing of black men who tried to access GI benefits; even the refusal of postmasters to deliver the application forms to black households.

None of this was accidental. All of it was planned, concerted, and condoned. The wealth of this country continued and continues to rely on the labor of an ongoing underclass, and that has been achieved through a history of brutal violence, political disenfranchisement, unequal policing, and many other policies official and unofficial. The voting laws of so many southern states are still designed with surgical precision to keep black Americans from the ballot box.

I could go into more detail, as could the Ner Shalomers who recently studied Reconstructing Judaism’s “Stolen Beam” curriculum on reparations, which we will offer again in the coming year. But you know the basics of this already; and I am still learning.

A national conversation about reparations is long overdue, and is of value no matter what solution comes of it. Because such a conversation is itself teshuvah. It will necessarily involve acknowledgment and hopefully apology, and not just economics. (But also economics, which are important as a matter of justice and equity.)

It was the soul-searching conversations about German reparations for Jewish Holocaust survivors that enabled Germany to do a hard reckoning with the unthinkable suffering they had unleashed and, ultimately, to come back from that abyss, and step onto the world stage in a new way. This cheshbon hanefesh – this soul reckoning – is a kind of conversation we have never had in this country, and in that speaking and in that listening is where the healing will take place.

As writer Ta-Nahisi Coates writes in his article, “The Case for Reparations”:

What I’m talking about is more than recompense for past injustices—more than a handout, a payoff, hush money, or a reluctant bribe. What I’m talking about is a national reckoning that would lead to spiritual renewal. . . . Reparations would mean a revolution of the American consciousness, a reconciling of our self-image as the great democratizer with the facts of our history.

I look forward to that reckoning; I look forward to living in that country and witnessing that spiritual renewal. May I merit living to see it.

As the rabbis of the Talmud knew, teshuvah is powerful. The late Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz talked in terms of almost physics. He pointed out that like the universe itself, our lives are driven by cause and effect. Harms cause more harms, like ripples in a pond. One cannot see the ultimate effect of the injuries we inflict or that are inflicted on us. But Rabbi Steinsaltz argues that teshuvah has power over the chain of cause and effect. While it can’t undo an action that has already taken place in the past, it can change that action’s meaning and power in the present moment – and on into the future. It can calm or even still the ripples. Rabbi Steinsaltz says, “In a world of inexorable flow of time, in which all objects and events are interconnected in a relationship of cause and effect, teshuvah is the exception; it is the potential for something else.”

Imagine that. The potential for something else. I think we have all become discouraged; we see bad policies, bad actions as inevitable. But maybe not. Maybe the next thing doesn’t have to be the next thing. The next thing can be different, better. Because teshuvah exists and has existed since before the beginning of time. It is teshuvah that is what makes a different future possible. It is teshuvah that can prevent the spiraling. Teshuvah that can enliven our imaginations as we peer elsewhere in the multiverse, and try to discern what this world might look like right now, how things might’ve come out if some of these Great Harms had never been inflicted. What might our country look like with more generalized and less localized prosperity; with leadership of every color and gender; with Native American cultural institutions thriving alongside the culture and institutions from all our other points of origin? What is the music we’d be making, the dances we’d be doing? What would our children be like? What would they learn in school? Who would our friends be? Teshuvah allows us this rare chance at radical imagination – not just what is the minimal fix for the problem at hand, but what is the generous, generative, creative world we can imagine. And once we imagine it, we can start steering toward it.

So my request of us all tonight is to be part of this discussion. That we learn, that we listen. That we bring our Jewish experience of both suffering and repair, and our compassionate hearts. As Rabbi Tarfon says in Talmud, we don’t have to be the ones to finish this work, but we’re not at liberty to sit it out either.

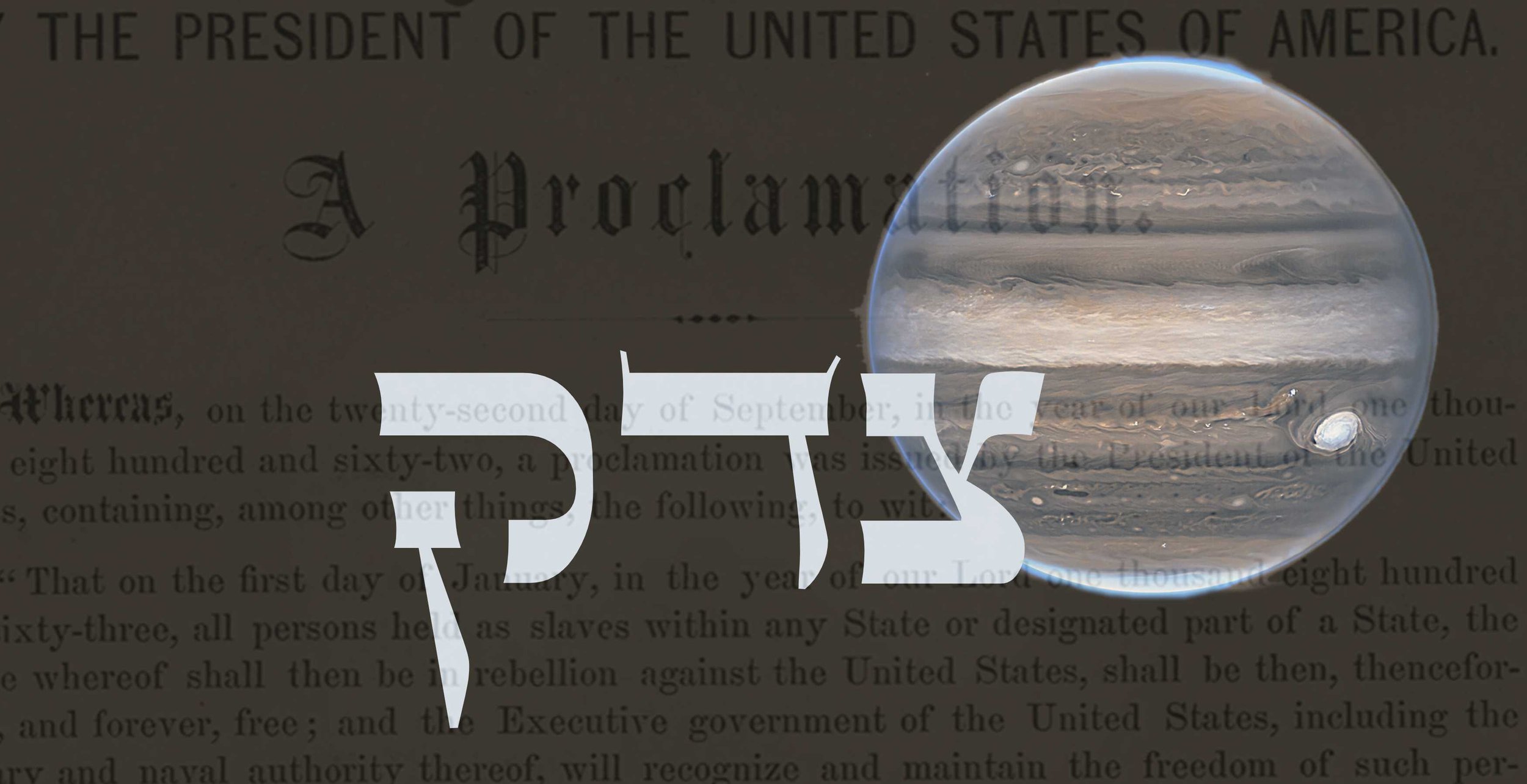

So right now at this very moment – and those of you at home on Zoom can look outside to see – the brightest light in the sky, after the growing Tishrei moon, is the planet Jupiter – which has rings, who knew? The name of this planet in Hebrew, since antiquity, is Tzedek, which means “justice.” Tonight it dominates the sky and sheds perceptible light.

I take that as a bit of encouragement. That justice need not be a slog or a struggle; it doesn’t have to be a battle cry or a wail of despair. It can be a light, a sweet light illuminating and guiding us even when things look dark. And behind it, there is teshuvah, old and abundant as the darkness itself, there when we need it, if we just remember . . .