Life is full of “what ifs”. What if I had done this? What if I hadn’t done that? A multiverse of possibility, of possible lives we could be living, of relationships we might or might not be in, the state of fulfillment and calm we would have or would not have achieved. What if? What if not?

The month of Elul is a time rife with such contemplation, as we think back on our year and on our lives and we wonder.

Examining the choices we’ve made necessarily involves asking “what if” questions over and over. What if I had handled that difficult moment differently? What if I had let go of trying to handle it at all?

Often the “what if” questions lead us down a path of regret or self-judgment, noticing all the things we might have done better. It’s equally legitimate in such a look-back to notice our strength, our resilience, and wonder about that with gratitude. What if I had not had the skills, the faith, the outlook to get through all of this? How would that have gone?

This month of reckoning has, as we know, its own special psalm: Psalm 27. And on this 27th day of the month of Elul, let us again take up this gorgeous, heart-filled, raw, and beautiful piece of holy poetry.

You regulars know that this is our third consecutive week of looking at Psalm 27, sharing a translation, and singing a verse or two. Two weeks ago we began with Adonai Ori v’Yish’i, the opening verse: “Adonai is my light and my help; whom should I fear?” And that week and last week we also sang Lakh Amar Libi Bakshu Fanai – “my heart says to you (or to me, in your name), ‘Seek my Presence.’” And last week we chanted Al Taster Paneykha Mimeni – “Do not hide Your Presence from me.”

This week we drop to the end of the psalm. The second-to-last verse, Verse 13, which reads:

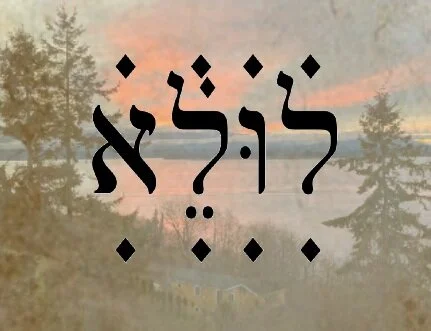

לוּלֶא הֶ֭אֱמַנְתִּי לִרְא֥וֹת בְּֽטוּב־יְהֹוָ֗ה בְּאֶ֣רֶץ חַיִּֽים׃

This is a tricky verse, mysterious, suggestive, and startlingly incomplete.

It begins with the word lulei – and old Hebrew compound, made up of lu, “if,” and lei, “not.”

Lulei: if not, if I hadn’t, if I didn’t, if something had not happened...

Lulei he’emanti – if I hadn’t believed, if I hadn’t had faith, if I hadn’t seen the truth in....

Lulei he’emanti lir’ot b’tuv-YHWH – if I hadn’t had the faith to see the goodness of Adonai...

B’eretz chayim – in the land of the living.

This verse seems to ask a not-entirely-clear “what if” question about living with faith. “If I had not had the faith to see the goodness of Adonai in the land of the living...”

What does it mean to see the goodness of Adonai in the land of the living?

The psalm could be expressing a cut-and-dried faith that everything God does is good, in a good-versus-bad, values-laden way. That would certainly be in keeping with theologies past. But that’s not an easy pill for us to swallow. We see suffering all around us; how can we have faith in God’s goodness? That kind of goodness?

God’s goodness has to mean something different.

So instead of starting with “goodness”, let’s start with “God”. The psalm uses the Divine 4-letter name, YHWH. This name doesn’t technically mean “God,” which in Hebrew is Elohim. And it doesn’t mean “Lord” as King James translates it, or as we ourselves imply when we substitute the word Adonai for it out of an old taboo against pronouncing it.

Instead, this mysterious name, YHWH, is a word that seems to contain the past, present and future tenses of the Hebrew verb “to be.” YHWH, if you had to translate it as a conventional word, would mean something more like Is-Was-Will-Be. Maybe “Timeless Existence” would be a reasonable translation of the Divine Name. Rearrange the four letters and you form Havayah, which rather elegantly means Being.

So with this understanding of YHWH not as Daddy-God but as Existence or Being itself, what might the psalm suggest about seeing the goodness of YHWH? Is there a kind of higher level goodness flowing in everything? In all that Is, Was, and Will Be?

I suspect many of us in this room have experienced moments of expanded consciousness, either naturally induced or not, in which we open to a feeling of connectedness with all things. That the Universe is of one cloth, and that it has an inherent wholeness, fullness, goodness to it.

Not necessarily “good” in a pleasant or easy way, or in a way that accrues to our happiness or is even in any way about us. But it is “good” in a vayar Elohim ki tov – “and God saw that it was good” – kind of way. A good that is not a value statement but an observation. An observation about essential wholeness; about the fact that we are all of the same stuff, linked, we and the earth and the stars, back to the Big Bang. We might personally sometimes suffer at nature’s hand, and yet there is a perfection in it too – from the power of the supernova to the workings of tiniest subatomic particle. All of it is at play, we are part of it, and it is good.

At this level of “good,” we are talking about something far greater than we conventionally mean by the word. And so “seeing good” in the psalm could refer to observing this cosmic wholeness, describing an experience of wonderment. Lulei he’emanti lir’ot b’tuv Havayah – what if I hadn’t the capacity to feel this wonderment?

If so, then what does it mean to experience this wonderment b’eretz chayim – in the land of the living?

Perhaps here the psalm is pointing to the task of integration. Not just experiencing wonder in those rarified moments of spiritual ecstasy or psychedelic expansion, but integrating wonder into all of our experience of life on this living planet. Infusing the day-to-day with wonder, making living in this world richer, even if living in this world is still difficult.

Oh, let me have that faith, that mindset, to experience the wonder of all that Is-Was-Will-Be, not just in dreams and visions, but right here in the dirt and muck and laughter and sadness and tangles of life. Because, man, lulei, if I didn’t have that, well... I don’t know.

I don’t know and the psalm doesn’t tell us. This remarkable verse of ours never resolves. It opens with an “if” and never offers a “then.” It just says, “If I didn’t have the faith to see the good in all that Is-Was-Will-Be, right here in the land of the living...”

Dot-dot-dot. Ellipsis. It just trails off. If I didn’t have this outlook, then what? I can’t imagine; I don’t have words.

This might be the psalm shrugging its shoulders and giving up. But I think this is the psalm inviting us in to answer the question for ourselves. What would my life be without that wonder?

There is a unique scribal anomaly in this verse. The word lulei is written with a dot above each letter and a dot below each letter. It is one of these inexplicable scribal traditions, thousands of years old, older than our Hebrew vowel system itself. Does it have secret mystical meaning? Or just a scribal one – some say the dots indicate uncertainty if the word should be there at all. What we know for sure is that those dots draw the eye like a ballyhoo of spotlights announcing a Hollywood premiere. If you saw a manuscript of Psalm 27, you would have no choice but to immediately zero in on that word, reading it aloud, and asking the question, “What if?” Or more precisely, “What if not?” Almost as if the question in this verse is the most important question for us to be asking.

And this is a timely invitation. The month of Elul is the time for considering our actions, our outlooks, our integration – all of it. Do it now, says the psalm, by highlighting the word lulei which is, coincidentally – or not coincidentally – the month of Elul spelled backwards. “What if not” is the question of the month.

I can tell you, without too much soul searching, that I don’t take nearly as much time as I’d like appreciating the wonder of this world. Dropping out of today’s particular aggravation or grief or Netflix show and noticing the particles and waves that operate the whole shebang, connecting me with the whole world and the distant stars. But I do appreciate this more and more, and it means something to me.

And lulei – if, God forbid, I did not have the ability to see the world in this way, then, well, I honestly can’t say.

I am indebted to my friend and mentor Rabbi Eli Cohen, who pointed out the dots, the Elul anagram, and the fact that this is a conditional clause whose conditions are never revealed, and challenged me to imagine why.

The chant of Lulei He’emanti that you will hear in the podcast version of this drash is by Rabbi Andrew Hahn, the Kirtan Rabbi. Listen to his recording of the chant on Soundcloud.

For a compendium of scribal anomalies in Torah, click here.

Wishing all readers a happy, healthy, safe year of endurance and awakening.