I. Ordination

I woke up early on the Sunday of my ordination – long before light, I was so wound up. I’d had a Zoom circle with a few friends the night before who offered me blessings. And the night before that I’d been celebrated at my Ner Shalom community’s Shabbat service. I was cranked and ready and tired of waiting.

But there was a long day still ahead. A ceremony in which teachers dropped into my Zoom breakout room to offer me their blessing. Then a ceremony created by the current students in the ALEPH Ordination Program to honor the outgoing students. A feature of that annual ceremony is each ordinee being led off for a private blessing by one or two students they’ve asked to play that role. This year there was no wandering off – we stayed in the Zoom Room – and the pair I’d invited called each other on the phone and then conferenced me in. There, each of them gave me a stunning blessing. One of the blessings was entirely culled from my own words, from the drashot I’ve posted here on this blog. This shook me. When I write words of blessing in my sermons, I mean them. But I’m also the writer and deliverer; I’m never simply the receiver. And hearing my own words of hope and intention reassembled and boomeranged back at me bowled me over. Out poured a river of tears.

At last it was time for the Smicha Ceremony itself. I chose to place myself in the Ner Shalom sanctuary, not only because it is lovely and feels like home, but as an invitation to our congregation to be with me in spirit, by connecting through the space that we all share.

Preparing the sacred space and holy technology. Memorabilia, snacks, kleenex, amaryllis.

I was well equipped. I had photos of my parents, and a memorial candle for my mother, whose yahrzeit would begin during the ceremony as the sun set over California.

I had a little bowl of family trinkets – including a locket and charm bracelet of my mother’s and the disembodied, painted-over mezuzah of my childhood home. I wore a tie of my father’s, a shirt given to me by my sister, and my great-grandmother’s engagement ring, ca. 1900.

I had an enormous amaryllis, given to me by my friend and neighbor Rick, grown from a bulb that his husband, my friend Richard, ordered last fall from Holland. Richard died during the early days of the pandemic, but the lavish red flower bloomed anyway, and Rick gave it as a way for Richard to bear witness.

What else? Creating sacred space in an empty sanctuary with computers and screens isn’t always easy! I had the Union Prayer Book my father received for his confirmation in 1940. I had on my shoulders a tallit that had belonged to my beloved childhood- and lifelong – rabbi, Mark S. Shapiro, loaned to me by his family, through the offices of his son, my friend Steve. Also at the ready were a bottle of Slivovitz and 6 shot glasses.

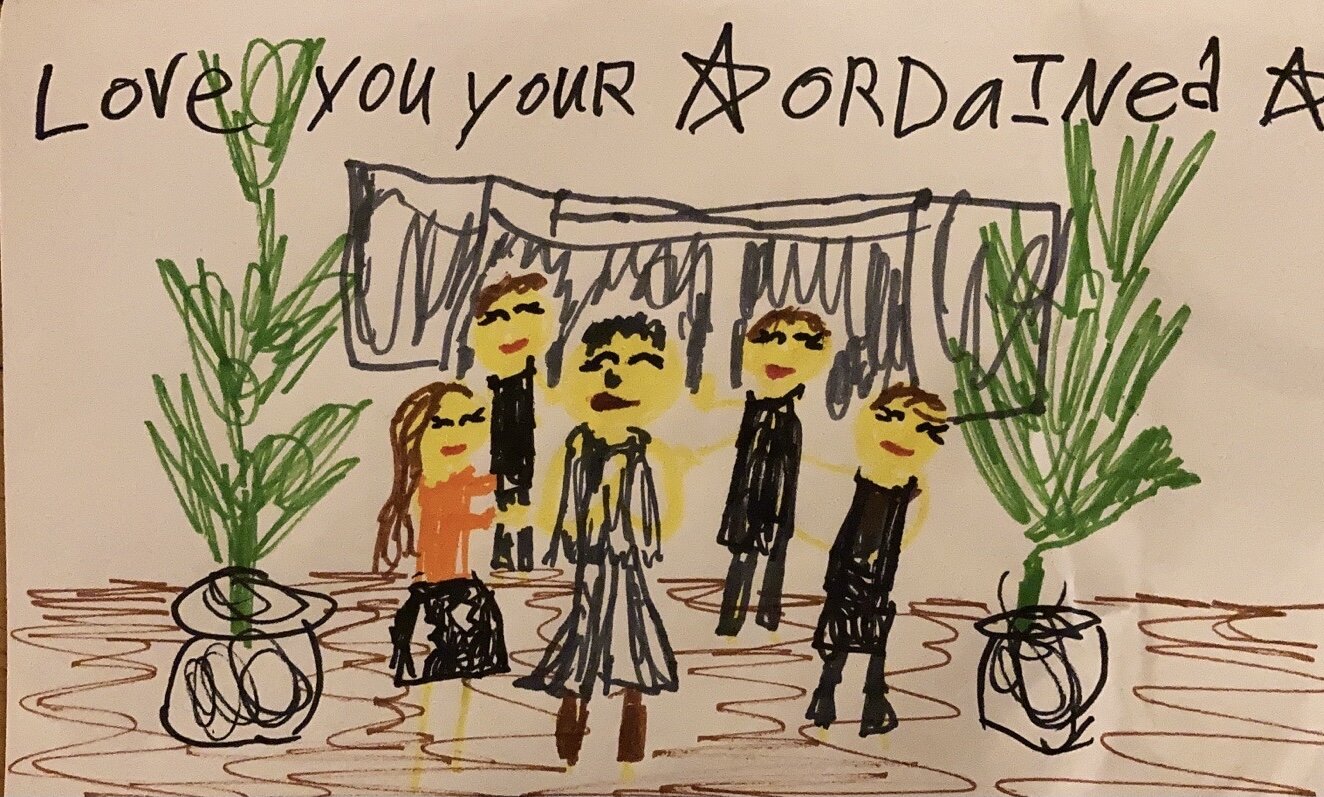

Six shot glasses, because I also had my family around me – Oren and Anne and Suegee and Ari and Doron. If this smicha had happened in the ballroom of the Omni in Broomfield, CO, as we’d all expected, I would’ve been on a stage and they would’ve been somewhere lost in the audience. Instead, I rested in the warmth and intimacy of their presence.

The ceremony had its technical glitches, keeping the proceedings lively. But we all settled into it. Each ordinee had 3 minutes to give over some Torah teaching. I had had trouble with this task. It is so much easier to write 1500 words than 300. I let this obligation simmer on a back burner, knowing I usually can’t write a drash until close to its delivery, because I need for it to be alive for me in the moment. But nothing alive was revealing itself. Finally, on Friday afternoon I remembered a favorite teaching from the Berditchever Rebbe that felt containable and also relevant to us, days after an insurrection at the US Capitol. It was a teaching about the Priestly Blessing, and how the posture we use to offer that blessing represents a way in which our actions inspire the participation of the Divine. (You can watch this on the video to the left.)

Birkat Hakohanim glove by Rabbi Marcia Prager.

At last it was time for the smicha, the “laying of hands” – the physical transmission of rabbinic authority from our teachers and their teachers to us. This was the first time the laying of hands was going to happen virtually. And I’m good with the virtual. But I also wanted some hint of physicality. So I’d sent a glove to each of four of my teachers, asking them to put them on, offer a blessing, write their name, and send it back so my family could wear them and put hands on me in their names for this transmission. Our dean, Rabbi Marcia Prager, took the request one step further, and designed and calligraphed the priestly blessing onto her glove. (See photo.) She had had no way of knowing I would choose to give a teaching on that very blessing.

We were each called up in turn and gave our Hebrew names. I chose to give my name in the new gender non-binary style: Yitzchak Eliyahu mibeyt Miryam v’Hillel HaLevi, with mibeyt – “of the house of” – replacing ben, “son of.” I added HaLevi to my father’s name, after having seen the grave in Germany of his great grandfather, my namesake, Yitzchak Keller, with a gravestone featuring the image of a ewer, a traditional symbol of Levites, referencing their sacred ancient role of washing the hands of the priests.

I stood and my family gathered and placed their hands on my shoulders and back and I received the transmission of my teachers. I imagined the Ner Shalom community gathered round. I saw Reb Zalman standing in the background, not too far. And I felt the presence of Rabbi Shapiro, whose tallit was wrapped around me.

At the end of the transmission, I was pronounced “Rabbi Irwin Keller.” I sat down and added the title Rabbi to my Zoom name, and began pouring the Slivovitz shots.

II. Lamentation

I woke up Monday to my first morning as a rabbi, trying to assess what felt different. After all, I had been serving as the spiritual leader of Ner Shalom for more than a dozen years. Nothing was changing in my employment or my deployment. But looking at the stationery my sister sent me that said “Rabbi Irwin Keller” was feeling like something. I read congratulatory messages, and engaged in the lively online assessments of the evening’s ceremony.

At noon I received an email from Eliot asking me to call him; there was sad news. I grabbed my phone and called my teacher Rabbi Elliot Ginsburg who seemed surprised to hear from me. In our shared confusion, I looked again at the email. It was not from him, but from Eliot Shapiro, Rabbi Shapiro’s second son, the brother of my friend Steve.

I called him back, with dread at my shoulder. He told me that his brother had had a heart attack that morning and had died. I gave an involuntary cry of shock, I’m sure the umpteenth cry of shock that Eliot had had to endure that morning.

Steve was beloved to many, including me. But this wasn’t a lifelong friendship. When we were kids, he was a year younger than me, which means we were never in the same Sunday school or Hebrew school class. And besides, he was the son of my revered rabbi. It was too intimidating to consider being friends with him, and so I wasn’t, and I missed out.

In 1981 we were both counselors in our summer camp’s Hebrew-speaking Chalutzim program. But even then we made it through a summer of working together without getting too close. I was, at the time, in the early stages of coming out of the closet, and was squarely in the closet at camp. And Steve was in some ways such a guy. I didn’t come out to him, which means I was withholding all summer long. With Steve, what you see is what you get. He was who he was thoroughly. And I wasn’t. And there was no place for us to meet.

But nine years ago, I was going to be coming through Minneapolis with the Kinsey Sicks. Steve caught wind of this and reached out to ask me to lunch while I was there. For a moment I felt all my layers of old hesitation. Then I said yes. At lunch I discovered a friend – someone so warm and so real. I realized with a shock how much I had missed. The next day he texted me how much fun he’d had, and that he hoped it wouldn’t take another 30 years to do it again.

Irwin and Steve, Jerusalem 2015

It didn’t. I saw him whenever I was in Minneapolis. I started visiting his parents when I was in Chicago and he would sometimes be there. He sent me words of comfort when my mom had her stroke. When Steve realized that I was in Israel at the same time that his family was there to celebrate his father’s 80th birthday, he engineered it for us to find each other outside the walls of the Old City for a reunion – their family and mine (I had 14-year old Ari and his best friend with me).

As his father’s health began to decline from Parkinson’s Disease, Steve stayed in close touch with me and I would offer him the best caring words I could muster.

Steve was the chief curator of his father’s legacy. He enlisted me in his project to publish his father’s sermons while his father was still well enough to enjoy the attention and the honor. Steve asked me to speak at his father’s shivah to convey what he had meant to my generation of kids, so many of whom had become rabbis. Steve called me a couple months ago because he had uncovered a new trove of his father’s sermons and wanted to know what I thought he should do with them – maybe a podcast?

When his father was dying in August, Steve asked me to make a video they could play for him. I was grateful for Steve’s deep mindfulness about his father’s experience and the experience of the community. He wanted people to get to say goodbye. I made a video. I sang and I told him what he meant to me. And I told him that I expected him to be present for me at my ordination in some way. It was still during shivah for his father when Steve offered to lend me one of his tallitot to wear for the ordination so my wish could come true, and I could feel Rabbi’s hands on my shoulders.

Steve was very enthusiastic about the ordination and the tallit project, sending me texts tracking its movement across the country. After it arrived, I told him I was spending time davening in it to get to know it better, and he was glad. Two weeks ago he emailed to ask if at the moment I receive my smichah it would be okay for him to shout out “You de Man!”

Steve was at the smicha Sunday night and witnessed what he had engineered – the last rabbinical passing of the torch from his father to one of us. Afterwards he texted me, “I’m proud to call you RABBI.” And Monday he was gone. A sudden, uncompromising blow to his family, who had just experienced such a huge loss months earlier. And an uncompromising blow to the hundreds of us who called him friend.

I missed out on so many years of friendship. And I was blessed by the warmth and gentleness of the last decade. He was a dutiful and loving son, a sensitive mover of people, and a warm, humble and thoroughly real friend.

His death was unexpected, although I wonder if caring for his father prepared him in some way. At his father’s shivah, Steve opened his remarks with Fiona Apple’s lyrics: “I have only one thing to do and that’s be the wave that I am and then sink back into the ocean.”

And that’s what he did. He was the wave that he was and now he is ocean. He shares my mother’s yahrzeit; I add his memory to hers. I think of him with love. Steve, You de Man.