Minnie and Irwin Keller, Chicago, 1940s or 50s

Isaak Keller, Frankfurt, 1940

There is a word in Spanish that I learned back in the 80s: tocayo. I was in Cuernavaca, visiting my aunt and uncle in the mostly gringo enclave they lived in. They brought me to a gathering at the home of friends, a Mexican Jewish family, transplanted from somewhere in Europe. The elders were Yiddish speakers, and the children of the family would ask Abuelita to pronounce the name of the nearby town, Cuautla, so that they could giggle when she delivered it back as Koytleh. At this gathering I was introduced to a young man with beautiful eyes who was, they told me, my tocayo. That is, his given name was Irwin.

I guess I knew the English word "namesake", and in fact my best friend in junior high was my namesake, another Irwin with whom I shared enough interests that we would have clicked anyway, but with whom there was the special bond of each being the only other Irwin we had ever met.

But tocayo, a Spanish word abducted from Nahuatl, felt different, stronger – more intimate and fateful than "namesake". Perhaps it was because this young man in Cuernavaca was so attractive and looked at me with such intensity that my heart began hammering a lifelong imprint of the word into my nervous system. Or perhaps because here in the silver-laced hills of Morelos, I never expected to find another Irwin; and so tocayo felt bigger than the mere happenstance of being namesakes. As if we were long lost kin, separated twins, the answer to a shared mystery, with each of us approaching the puzzle from a different direction, like digging a tunnel under the English channel, one team starting in Dover and the other in Calais.

Irwin.

I grew up with this name, this out-of-phase name, because of the death of my grandfather, Irwin Keller. He died three years before I was born, and I would be the first grandchild to appear since. My parents didn't publicly commit to the name beforehand, although when discussing options, my now-widowed Grandma Minnie would gently chime in with, "You know – Irwin's a good name."

Having never known Grandpa Irwin, the name-sharing did not weigh too heavily on me. Every once in a while I would find something in the basement that had been his, with his name written, embossed or engraved on it, and it would get my attention and spark my wondering. Grandpa Irwin wasn't talked about very much. Not, it seemed, because he was a difficult topic, but because he wasn't. Life had simply moved on and he wasn't in it.

But while sharing a name with a dead grandfather was not itself a burden, bearing that particular name was. It belonged to an earlier generation, which worked fine at family gatherings, where I preferred to sit with my grandparents and their siblings anyway. But it was troublesome at elementary school where I was perennially the only Irwin, and my name could easily be weaponized as a taunt.

In fourth grade I started Hebrew school, and needed a Hebrew name to be called. My mother unearthed the certificate from my bris, which revealed my Hebrew name to be Yitzchak – Hebrew for Isaac, a name that brought with it a rush of Torah associations: the child walked by his father to the brink of his own undoing, the young man with a wife chosen by a servant, the baffled middle-aged father who could not tell his children apart.

Grandpa Irwin had never, to anyone's knowledge, had a Hebrew name. Even his 1902 confirmation certificate from Chicago's Temple Emanuel was silent on the subject. So to my mind, Yitzchak was an improvisation, an impulse, on the part of the rabbi presiding at the bris.

Over time, however, I came to appreciate that the rabbi's decision was not random. There was a near 1:1 correspondence between Old Country Jewish names and their secular equivalents adopted in the US. Every Moshe became a Maurice. Every Chaya became Ida. Nearly every Yitzchak became Irving (if Russian) or Irwin (if German). The choice of “Yitzchak” for me was convention, not caprice – an ethnic retrofit.

But when, as a middle-aged adult, I looked for the first time at the death certificate of Grandpa Irwin's father, Herman Keller, and saw that his father was listed as Isaak Keller, I gasped. In that moment I understood that my Grandpa Irwin, after whom I was named, was in turn named after his grandfather, Isaak Keller. His name, Irwin, was indeed a secular veneer over a deeper, underlying Yitzchak. We were three waves of Yitzchak Kellers, leapfrogging generations. My grandfather, and my great-great grandfather, were my tocayos, reaching forward to me through time as I reached back.

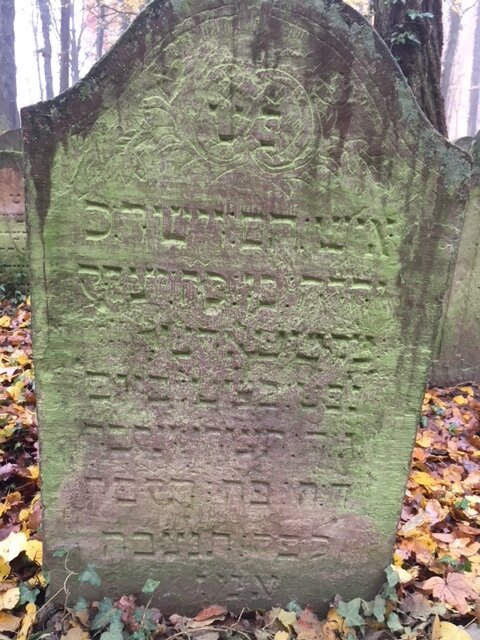

Two years ago I visited the town in southwestern Germany where the Kellers were from, a place of origin I’d only discovered weeks earlier. A day after my arrival I stood at great-great grandfather Isaak Keller's grave on a drizzly hilltop halfway between Mannheim and Stuttgart.

Yitzchak ben Yehudah it said on the front face of the monument (underneath the carved image of a ewer, signifying the tribe of Levi) and the curiously spelled Isack Keller on the verso. But that wasn't quite journey's end. Because Isack Keller's father, Judas, was also buried there. I found his stone too, legible despite his having been buried 190 years earlier. And there I saw his patronymic for the first time: Yehudah ben k'vod harav Yitzchak. Judah son of Rabbi Yitzchak. Yet another leapfrogged Yitzchak, making me the fourth of these, hopscotching through the generations of our family, each named after a grandfather we never met.

I know virtually nothing about these German Yitzchak ancestors. I've seen their village now and that enlivens my imagination. But I don't know if they were short or tall, warm or withholding. I might look nothing like them; I might be nothing like them. I could actually have very little of their DNA. But I know for a fact I carry their Y-chromosome, which comes straight down the male line. If I'd known it, I might have shared with them the experience of being a Levite. And, I guess I do share with these grandfathers the identification with a biblical boy, bound to a stone by his father, rescued by an angel.

One Yitzchak, though, was not rescued. After my great-great grandfather, Isaak Keller, died in 1874, at least two of his children named sons after him. My own Grandpa Irwin, born in America, was one of these. Another was Isaak Keller, born in 1877 in Gross-Gerau, outside Darmstadt, along the Rhine. I saw his name somewhere a couple years ago, and threw him onto the family tree. But I only came back to him over this quiet Thanksgiving weekend, where I allowed myself to poke around on the various genealogical websites. Ancestry.com was throwing "hints" at me, fast like batting practice.

I was still in the batter's box when Ancestry tossed me a reference to that Isaak Keller, clearly him, with the right birthdate and the right parents. The document Ancestry had found was a death record. 1942. Dachau.

I saw, and sat in silence, breathing heavily. The Kellers had always seemed somehow immune to the Holocaust. My branch had come to the US in the 1870s. But now I saw this. Not just any Keller, but a tocayo. One with whom I can't help but identify, knowing how we share that name and that chromosome and that identification with the bound boy.

I imagined someone with my own name at Dachau, and felt ill. With investigation it got worse. Isaak Keller had been imprisoned at Dachau, but was ultimately murdered at Hartheim Euthanasia Center – a worse place than Dachau, if such a thing is imaginable.

I wondered about my own Grandpa Irwin Keller. Did he know that his first cousin and namesake, Isaak Keller, was murdered? If so, who brought the news to America? Did he and Grandma Minnie talk about it? Did they tell my father, only 17 at the time? Or did the Kellers of Chicago have no remaining contact with the European family left behind 70 years earlier, never learning about this at all? Was the Shoah for them a shadow, a free-floating fear, without the gruesome anchor of a specific loss?

How strange this world we live in now, when snippets of a person's life can flow so far beyond their timely or untimely end. How strange that it can turn out that I am the first to have a long enough view to see the landscape of Yitzchak Kellers – their journeys, lives, deaths. The ones whose Judaism was casual and genteel. And the ones whose Judaism was a death sentence.

I have a mental picture, a big picture, that my father did not have; nor, perhaps did Grandpa Irwin. I want to show them, to tell them! I want them to know what I've found, and to see what light it might shed on their own lives! But they are all gone. If death is one kind of thing, then it's too late. If death is a different kind of thing, then they already know.

In truth, all I can do is look at the light this shines on my own life. On the forces and circumstances that have allowed me to live in this particular place and time, with all its freedoms and all its risks. I live this particular life, carrying forward a name that has been borne, in some version or other, by all those versions of me – my tocayos over time and distance. And I find I am doing so, belatedly, with some level of pride and purpose.

As Grandma Minnie would've said, "You know – Irwin's a good name."

Grandpa Irwin H. Keller, confirmation photo, Chicago, 1902

Grave of great-great-grandfather Isaak Keller (1798-1874). Waibstadt, Baden-Württemberg

Grave of Judas Keller (1726-1827). Yehudah ben k’vod harav Yitzchak – Yehudah son of Rabbi Yitzchak.

Isaak Israel Keller’s Kennkarte (identification card) reprinted from Alemannia-Judaica.de.