And it’s a wrap.

The papers are signed. The inspections inspected. The repairs repaired. The movers have loaded 42 boxes, 2 suitcases and 3 pieces of furniture onto a truck in the driveway, drawing to a close the life of the Keller family on Osceola Avenue. Three years ago, the house was full of life: 55 years of life lived. Plus another half century of accumulated history in boxes piled high in the basement.

In the two and half years since our mother died, Lynn and I have come back repeatedly to make headway. To sort, curate, designate, and haul. And the house – not the frame but the content, not the body but the soul – has effected a kind of tzimtzum. A contraction. Each time we were there, the house would recede some. As if wondering about its own existence and finding it no longer necessary. And with this trip, with these last things removed, poof, what was the Keller house has finally disappeared altogether.

Over this time, every piece of furniture was considered, offered, allotted and carried out the door. Every piece of paper was reviewed, read, released or retained for one or more rounds of future consideration. Every photo was appreciated; the life of every forebear – parents, grandparents, great grandparents, great aunts and uncles – examined, discussed, and liberated from forgetfulness like an egg broken into a bowl on a hungry winter morning. The physical objects of my mother’s life have been dealt out like cards to many players: friends, cousins, charities, theaters, libraries, untold numbers of strangers, many of whom came to the house and, in bittersweet exchange, shared their stories and how the bed-computer-chair-coatrack would change something for them.

The work was not steady or linear. We’d do 5-day spurts; maybe an aggregate of 6 weeks of labor since the summer of 2014. We would swim upstream through symbolism and memory. We’d get momentum and we’d get sidetracked. There were a million instant research projects, trying to crack the mysteries of unidentifiable things: people in photos, sources of memorabilia, the meaning of markings on silver platters.

Wednesday was the last such research project, with inconclusive outcome. It was to determine the provenance of a quilted bedspread folded and wrapped in plastic. It had been folded and wrapped in that same plastic for as long as Lynn and I could remember. Neither of us knew whose it was or how it came into the house and there’s no one left to ask. But there was a dry cleaning tag on it. “North Chicago Laundry,” it said. And there was a phone number on the tag: Bi8-3210. No one has advertised phone numbers with letter prefixes since the end of the 1960s. So it’s been there, clean and wrapped, for at least that long.

The dry cleaning ticket was a clue. If we could work out where this laundry was, it might tell us whose bedspread it was, since no city dweller walks more than two blocks for a dry cleaner.

With Google’s help, we searched the name of the laundry. Too generic. Then we tried to determine which neighborhood had been the Bi8 telephone exchange. Because sometimes the exchange name itself was the neighborhood’s name. Like "Diversey" or or "Hyde Park". So what was Bi8?

Lynn and I both remember the days of letters in phone number prefixes. Our own telephone number, as we first learned it as children, began with YO, for Yorktown, although there has never been a nearby anything called Yorktown. Skokie was OR, for Orchard, and we allowed that there might once have been orchards where now Jews grew like so much fruit. And the exchanges in the city? I had no idea what they stood for; they just helped me remember phone numbers. Aunt Hattie was EA7; Aunt Birdie GR6.

As this tangent ruptured our planned work, or at least mine (Lynn had moved on to puzzling over fragile 78-rpm records) I learned that Illinois Bell, in the 1920s, adopted a calling system for Chicago that involved 3-letter exchanges followed by 4 numerals. This limited each exchange to 9,999 phones, for instance EAS 0001 through EAS 9999. But the City was growing!

In 1948, Illinois Bell increased the available phone numbers tenfold by switching to a system of 2 letters and 5 numerals. The existing exchanges were slimmed down to two letters, and the third letter numericized. Now each exchange could have 99,999 phones! But at the beginning, that first numerical digit following the two letters was still just the equivalent of the letter that had been there in the exchange’s name all along. The EAS of “Eastgate” became EA7. GR6 was a restatement of the old GRO, for “Grovehill.” Complete 7-digit numeric dialing only became available on September 11, 1960. But my parents wouldn’t notice, being busy in the hospital welcoming their new son.

And Bi8, the exchange for our mystery laundry? It was the new articulation of BIT, short for “Bittersweet.” It seemed unrelated to any actual place. Perhaps it was just plucked from the AT&T list of recommended exchange names (yes, there was one). Either way, we were now chasing a bedspread back to a dry cleaner at Bittersweet 8-3210.

At last we found the goods. The bittersweet exchange was Near North, Lincoln Park-ish; and we discovered the laundry at 2901 N. Clybourn. Who in the family lived near there? I can’t imagine. Not a neighborhood I remember visiting as a child. Maybe I’ll return to this mystery when I get back home, when the boxes arrive, when there’s a chance to look through Mom’s (and Grandma’s) old address books, now somewhere in a moving truck. Most likely, I’ll never know. And that’s a sensation I’ll have to get used to. All the grounding objects and personalities of Osceola Avenue are now free-floating. Contents of boxes have gotten mixed or combined in packing, and in doing that we’ve deprived ourselves of future clues. From this point forward, it will be hard to say, “This came from Aunt Hattie’s house.” On the other hand, it will be easy and true and all that’s necessary to say, “This came from Marilyn’s.”

The famous basement is empty. The bedrooms; the kitchen too. The patio is bare, the grass overgrown. It’s done. This home is gone; it has withdrawn from that physical structure and from the world. Going forward it can only be carried in our hearts. This isn’t news. It’s just that today is the day beyond which any other illusion cannot be maintained.

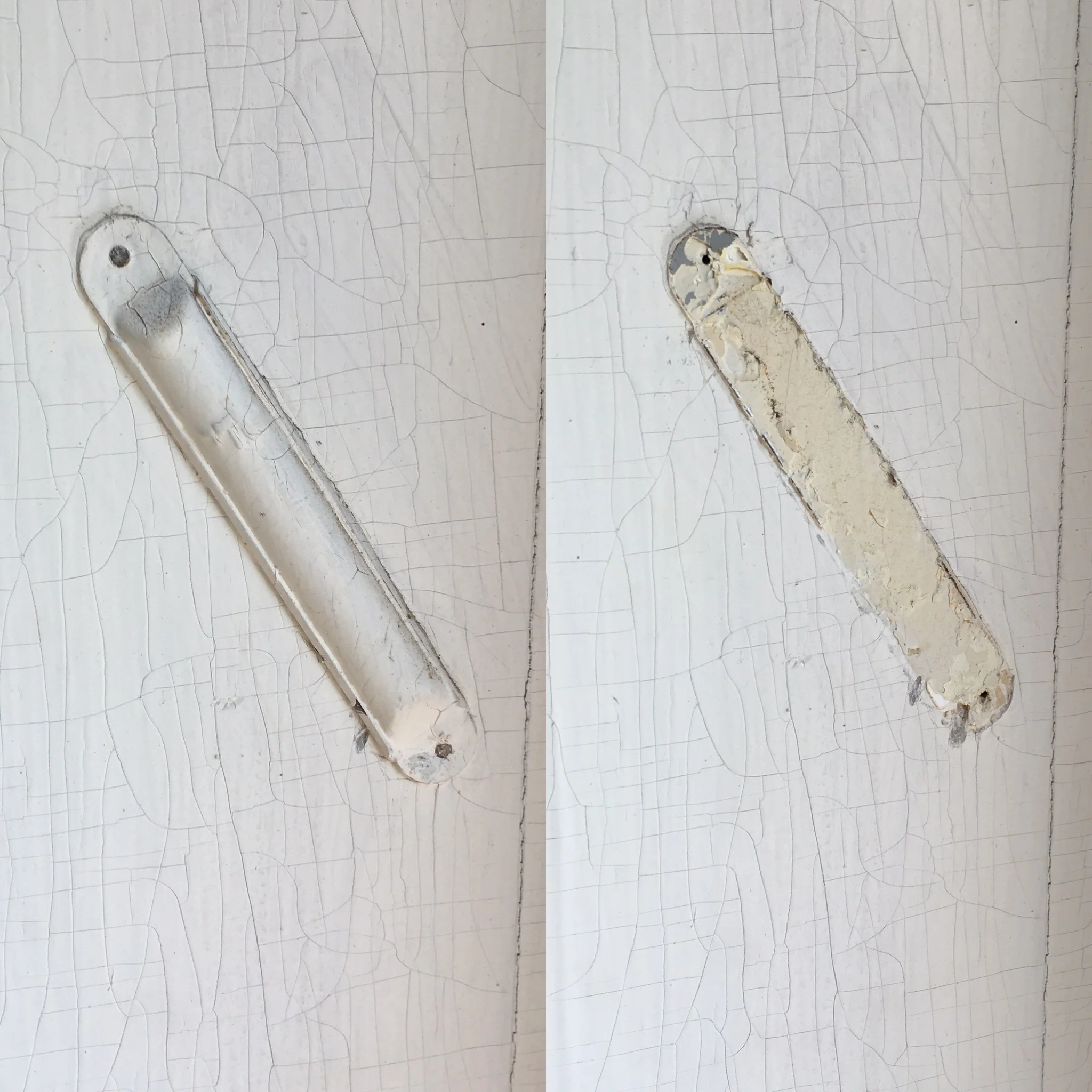

As I walk out the door for the last time, I instinctively place my hand on the doorpost, in the spot where the mezuzah had, until this week, hung. I know it is our custom to touch the mezuzah to invoke the Divine in our comings and goings. But in this moment I realize we also do it to invoke home itself.

All things change. People come and go. Losses are inevitable; we all experience them. The New edges in and considers the vacant space. Light gives way to dark and back to light. Life breathes us in and breathes us out again. An easy, bittersweet exchange; sad, rich, beautiful, inescapable.