[Drash for Congregation Ner Shalom, June 4, 2010.]

I was in Boston early this week for a Bar Mitzvah – the son of my oldest, dearest friend. It was a Monday morning event (which can happen in communities where Torah is read also on weekdays).

I was somewhat of an honored guest it seemed, so they asked me to participate in the service. Being nothing like shy, I of course said yes, offering to sing or improvise something – the kind of thing I would normally do here in our community. But the night before the Bar Mitzvah, my friends told me that they’d slated me in the program to read the Prayer for the State of Israel. It was already in print.

I took a deep breath and thanked them for the honor. Now if I were being asked to create a prayer for the State of Israel, this would have been an easy request. Israel is always in my prayers. But I was being asked to read the words in the Conservative siddur, which step slightly beyond a plea for safety, survival and peace:

Chazek et y’dey m’giney eretz kodshenu va’ateret nitzachon t’atrem…

“Strengthen the hands of the defenders of our Holy Land and crown them in victory.” Of course, I could understand nitzachon, “victory,” in metaphoric terms, but the prayer doesn't seem to. Victory here is an unqualified absolute, giving the prayer an undeniable military flavor that does not easily roll off my tongue. Nonetheless, this was my assignment in a ritual not of my making.

Monday morning I woke up to dress for the Bar Mitzvah and learned that during the night Israeli soldiers had boarded a ship headed for Gaza, in international waters. A peace convoy, some would say. A provocation, others would say. Predictably, it had all gone terribly, terribly wrong, leaving nine civilian activists known dead and Israel once again as the focus of the world’s scrutiny.

I tried to collect myself. I was filled with sadness and anger and a feeling of betrayal. How can the Israel that I love – and I do love it even when I am outraged by its actions – let this happen? My anger is understandable to most of you in this room; we are generally progressives in this community, and often critical of Israeli policy. But the internet war had already begun. YouTube videos of uninterpretable scenes were being posted, and emails started arriving in my inbox telling me to wait for all the evidence to be in (which was reasonable) and urging me to defend Israel against those who would slander it – and that “slanderer” part felt, as it always does at such moments, aimed at me.

I tore myself from the news and, heavy hearted, went to the Bar Mitzvah. I sat down in shul and listened to my friend’s son’s fluent chanting of this week’s parashah, Shlach Lecha. In Shlach Lecha the Israelites are preparing for the conquest of what will become the Land of Israel. God tells Moshe to send margalim – “scouts” - one from each tribe, up into the land to determine if its inhabitants are strong or weak, good or bad, if the cities are open or fortified, if the soil is rich or poor.

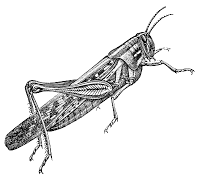

The margalim return, famously reporting that the land is flowing with milk and honey. Two of the scouts, Caleb and Joshua, are confident about their military prospects. Caleb, says, “Let us go up and gain possession of the land, for surely we can overcome it.” But the other scouts dissent. “We cannot attack, for the people are stronger than we. The country devours its settlers. The people are giants – and we looked like grasshoppers to ourselves, and so must we have looked to them.”

These words spread through the camp and the Israelites lose their nerve. They beg to be brought back to Egypt. God is angered and punishes the people by declaring that the older generation would die in the wilderness. Of all the people assembled, only Caleb and Joshua, with their great confidence in the strength of Israel would be allowed to enter the land.

I sat and listened to the parashah, thinking how we, all these years later, have possession of that very same real estate. So which are we now, I wondered, grasshoppers or giants?

It seemed to me that as possessors and not the dispossessed, it would be easy to cast us in the role of giants. Certainly much of the world paints Israel that way. But I’m beginning to think that after two thousand years of relentless conditioning, however we might be perceived by others, we still don’t know how not to be grasshoppers.

To a grasshopper, every encounter with the greater world involves the risk of being crushed underfoot. And hasn’t this been the Jewish experience over the last two and a half millennia? The risk of annihilation at every turn? We tell our tales of exile and pogroms and close escapes and failed escapes. We pray for peace; we pray to God to confound the counsels of those who would do us harm.

But nothing in our tradition has taught us how to hold power. How to be giants. Instead, we’re left to be giants who think like grasshoppers, or grasshoppers who have grown to gigantic proportions. And it is that constant, deep fear of being crushed underfoot that has informed and, arguably, poisoned so much of our policy in Israel.

I should footnote here that I say “our policy,” not “their policy.” I think it’s important both to say and to let ourselves actually feel the “we.” It is important that even when we oppose Israeli governmental policy – especially when we oppose Israeli governmental policy – we reaffirm our connection as Jews. It is what makes our voice of opposition powerful and meaningful; it is also how we support Israelis who are working for peace. Our inclusion is what we were promised by the Zionist dream when we were young. We were promised that this would be a joint venture. We should not now cede that promise only to those who agree with Israeli military actions. In other words, more than I want to disown Netanyahu, I want Netanyahu to be stuck with the likes of us.

I also need to offer the obvious but very real disclaimers. I do not live in Israel, although I have in the past and many of my loved ones do now. I’ve never had to fear suicide bombers on a daily basis and I’ve not experienced the relief of knowing that a wall currently stands between me and that particular danger. I’ve never had to dodge the bullets; nor have I been required to fire them. I am not a politician or an expert. I cannot speak from the depth of Israeli experience. But that doesn’t mean I have nothing to say.

I also don’t know what happened on that ship. Time will (or won’t) tell who did what to whom first. But I do know that it was a no-win situation, as long as we were in a position where a humanitarian action against us was necessary. Yes, the flotilla was at least as much or more a public relations mission as it was an aid mission, as some people hasten to point out. But so what? Sit-ins at lunch counters in the 1960s south were public relations stunts also. That is how public opinion is swayed, it is how one appeals to the hearts and consciences of the world.

Using deadly force against a public relations mission is the sign, to me, of government by grasshopper. To Israel this flotilla looked like another shoe about to crush us. Everything looks like a shoe about to crush us. Give a grasshopper a gun, and what will it do? It will shoot. If not today, then tomorrow.

A giant, on the other hand, well, giants are perhaps underestimated. A giant who understands and trusts its own power can afford a far greater range of responses to seeming threats. The use of force would only be one possible response among many.

In an Op Ed column on Tuesday, Israeli author and peace activist Amos Oz wrote, “[D]uring Israel’s early years, prime ministers like David Ben-Gurion and Levi Eshkol knew very well that force has its limits and were careful to use it only as a last resort. But ever since the Six-Day War in 1967, Israel has been fixated on military force. To a man with a big hammer, says the proverb, every problem looks like a nail.”

Defenders of Israel’s actions this week point to the rise of Hamas in Gaza. This is true and I do not suggest that Hamas is not a danger. But we are also smart enough to know that those whom you besiege do not become your friends. When you starve a people you cultivate a population with nothing to lose. On the other hand, in a prosperous, flourishing Palestine, how sexy would Hamas actually be?

Defenders of Israel’s actions also point to the fact that Gaza has two borders – one with Israel and one with Egypt. And Egypt was not opening its border either. In other words, it is unfair to hold Israel to a higher standard than other nations. Perhaps that’s right. The world does not have the right to hold Israel to a higher standard. But we do. Jews do. We are not accountable for Egypt. But for Israel we are. Again, it’s part of the agreement.

So I seem to be mostly talking about our right, as Jews, as people who want Israel to survive, to dissent. Because that no longer feels obvious. But I’d intended to talk about grasshoppers.

And so, young grasshoppers, courage is required. Not the courage to use force. But the courage not to. The courage to dream up other paths and to actually risk taking them. The courage to engage in peacemaking – real, non-grudging peacemaking – and earn back the world’s trust. The courage to help our neighbors and former enemies prosper. Maybe we can’t put down the guns entirely at this moment. But surely we can move our fingers off the triggers, even if just a little.

It will take more courage not to use force than it does to use it. It will take greatness. And I still believe we are capable of greatness; of the greatness of giants. We are already giants in military might. Let us soon be giants in wisdom and compassion and vision and patience.

You may wonder what I did about reciting the prayer for the State of Israel on Monday. I thought of some language I could add, like I might naturally do here at Ner Shalom. I was asked to deliver it in Hebrew so I thought, well, who will notice? I got up on the bimah and began the prayer. But this was a community where everyone prays in Hebrew. With my first word they joined me and recited with me, every word. I was walked down the path of this text, accompanied on all sides, with no chance for a detour. Which is exactly how it should have been at that moment.

But now I’d like to return the Prayer for the State of Israel, not how it was written in that siddur but how I wish it were written.

Avinu Shebashamayim,

Rock and Redeemer of the People Israel;

Bless the State of Israel.

Enrich it with Your love;

spread over it the shelter of Your peace.

Guide its leaders and advisors

with Your light and Your truth.

Help them with Your good counsel.

Strengthen our hearts and hands,

so that we may not be devoured by the land;

so that we may not be devoured by fear.

Crown us with courage

so that we may be giants of wisdom and compassion.

Bless us with vision, so that through us

and all who are touched by your spirit,

there may be lasting peace and joy in the land

and throughout the world.

And let us say: Amen.