I have seen the cavalcade of Bernsteins and Einsteins and Feinsteins. The Marxes - both Karl and Groucho. The Emmas - both Lazarus and Goldman. Bad Jews all. But all standing right there on the rusty tracks with us planting seeds in this new garden of ours.

Read moreA World of Teshuvah Ticklers

For Congregation Ner Shalom, Selichot, September 24, 2011

We think of teshuvah as an activity of limited duration - like an NPR pledge drive or a back-to-school sale, lasting from the beginning of the month of Elul through Yom Kippur. But our tradition teaches us that teshuvah can be done any day, any hour, any moment. Our introspection and return to our better selves will be accepted by God, if you will, or will be successful and transformative, as long as it is done wholeheartedly. Or brokenheartedly. Just not half-heartedly.

Healing relationships, fixing what we've broken through our actions, committing to try not to keep repeating the same mistakes - these are worth our attention any day, any hour, any moment. But the trick is to remember to do it.

The Ba'al Shem Tov had a practice. He would use the conduct of others as his invitation to engage in teshuvah. So, for instance, when he saw someone around him being angry without cause, or impatient with a loved one, or dishonest with a friend, instead of responding with anger or judgment, he would ask himself, "When have I been angry without cause, or impatient with a loved one, or dishonest with a friend?" Usually, he wasn't at a loss for an instance of exactly that behavior. And he would use the opportunity to make teshuvah. Instead of adding to the pain of the world, he would take the moment to take from the pain of the world.

As some of you remember from a High Holy Day sermon a few years ago, I've tried to adopt a similar practice in the privacy of my car. I always think that driving a car is one of our purest tests of teshuvah. We interact with other drivers, but we are isolated and anonymous - a combination not necessarily designed to bring out our best. So when someone cuts us off carelessly or drives slowly because they're lost and trying to read the street signs, we experience greater freedom to steam or curse or use our hands in especially creative ways. So I try to take the moment to remember the last time I did something stupid or even careless in the car, or was lost and trying to read street signs as traffic piled up behind me. My moments of car-teshuvah calm me and draw from me qualities of empathy rather than anger - which I'm happy about. The roads are paved with enough anger already.

(A cobbler - channeling divine hints?)

Other Chasidic masters found other ways to remember the task of teshuvah. They looked for messages, for reminders, embedded within the day-to-day.

For instance, Rebbe Levi Yitzchak of Berditchev, it is said, was standing in his home, looking out at the street one year on the 1st of Elul. A shoe repairman came up to the window and asked him, "Don't you have something to fix?" The Rebbe immediately began to weep. "The Day of Judgment is approaching," he said, "and I still haven't fixed myself." And he moved into teshuvah.

Rebbe Simcha Bunim of Pshischa went to the market and wanted to buy something a farmer was selling. The rebbe and the farmer haggled, but they couldn't come to terms. Then the farmer looked the rebbe in the eyes and said to him in Polish: "do better," by which he meant "offer a better price." But when the rebbe returned home he thought to himself that "do better" meant something else: even the farmer was encouraging him to better himself and his deeds, or God's demand was coming to him through the guise of the farmer, and that the time had come for teshuvah.

Once you start looking for these messages, you'll find them everywhere. Like today on my airplane coming back from Boston. We hit a nasty pocket of turbulence just at the moment the flight attendant announced, "This will be your last chance to throw away any garbage." And as my heart beat in fear - I know planes don't fall out of the sky because of turbulence, but it always feels like they will - she repeated, "This will be your last chance to throw away any garbage." And I turned to a moment of teshuvah because, I thought, you never do know when your last chance will be. There is never a reason to wait.

This is the conclusion of another Chasidic story about the famous brothers, Rabbi Elimelech of Lizhensk and Rabbi Zusia of Hanipol, who would travel together incognito to better learn the needs of the people. One night they asked for hospitality at a small house. The balabosteh, the lady of the house, fed them and found them a place to sleep, explaining that her husband was away working until very late. The brothers went to sleep but woke up near midnight when they heard her husband come in quietly. He sat down at the table in the candlelight to sew up a hole that had torn in his coat so he could wear it again in the morning. His wife whispered to him, "Repair it quickly, while the candle is still burning."

The two brothers heard in this a holy insight: you must fix what needs fixing during this life. There is no other time to do it. Do your teshuvah now, before the candle goes out. Because teshuvah is available every day, every hour, every moment. We just have to remember.

Teshuvah can be a joyous engagement. We can enter with gratitude - that we have better selves to aspire to be, that we have relationships worth repairing, that we care about who we are in this world. So let us do our teshuvah with joy, with gratitude, with or without traditional language or Hebrew words, so that our presence on this planet will be a blessing.

This piece draws strongly from the wonderful material in Yitzchak Buxbaum's Jewish Spiritual Practices.

Teshuvah, Gratitude and First Fruits

For Congregation Ner Shalom, September 16, 2011

This month of Elul is a fascinating time. We describe it as "contemplative" since it's already high teshuvah season, "atonement" season for lack of a better word. We are engaged, or encouraged to be engaged, in chesbon hanefesh - our own personal moral reckonings. And to heal rifts with others - our loved ones and sometimes our not-so-loved ones.

Teshuvah is a process that feels very private and contained. The sound of teshuvah is a kind of hush. It has an inward focus, a deep interiority, even when it involves others. In fact that's one of the things that makes teshuvah such a hard task, because it calls on us to build a bridge from our own interiority to the interiority of someone else. Not a meeting of the minds, but an uncharacteristic, often very engineered meeting of the hearts.

Teshuvah is a hard, sometimes painful task. It always feels like the right thing to do, but it does not have a high desirability quotient. We avoid it, or we force ourselves to do it, sometimes at the very last moment, only when push comes teshuvah.

So imagine my surprise recently when I stumbled on a quote from the early Chassidic master, Yaakov Yitzchak Horowitz, the famed "Seer of Lublin." He gave this instruction:

When you pray about teshuvah and you express your hopes, you should say that you want to repent out of joy and expansiveness and amidst bounty, not from sadness and stress and in need and poverty.

I thought, how can this be? Asking for our teshuvahto come from a place of joy and expansiveness and bounty? Because for me teshuvah is all about getting smaller. Contrition feels like contraction. Atonement is about becoming "one" again after some spiritual scatteredness. The word teshuvah describes the act of returning - to the core, to the center of one's being, after wandering. We know how humbling the act of apology is, and taking account of our shortcomings inevitably makes us feel small.

But here the the Seer is suggesting that our goal is to do our teshuvah from a place of expansiveness and abundance. How is this possible to do?

So for guidance I did as I often do and checked out the week's Torah and Haftarah portions, to see what light they would shed. Now these are not pieces of Torah that are about teshuvah or about Elul. In fact, the Torah portion contains the instructions for observing the pilgrimage holiday of Shavuot, a holiday that we left behind over three months ago. And it is certainly odd that we end up reading about Shavuot not during Shavuot but on the eve of the New Year, just the way we read about the Exodus not during Pesach but midwinter. Such is our cycle of Torah reading. But this mashup of two moments - a lived moment and a narrative moment - has been ratified by thousands of years of cyclical Torah-reading. So by this point, looking at how Shavuot ritual and Elul intention dance together is certainly justified.

So I looked at our Torah portion, Ki Tavo and I looked at our Haftarah portion, from Isaiah. And there they were - both surprisingly beautiful and uplifting and full of light and hope.

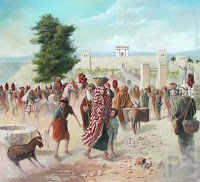

I'll tell you first about Ki Tavo and its instructions for Shavuot. In Biblical times, Shavuot was a chag, or hajj. A pilgrimage festival, meaning that a pilgrimage was required. To Jerusalem, so that one could walk up to the Holy Temple itself, the heart of our people, the heart of holiness, and offer the first fruits.

(Bikkurim - first fruits - by Estair Kaufman)

So I'll let you imagine it. It would go something like this.

As the first fruits of your field begin to sprout in early spring, you would tie a piece of papyrus around the stem so that you'd remember which were first to emerge. When ripe, you'd picked them. You'd pack them up carefully and head to Jerusalem, which would be full of people from all over the land.

On the day of Shavuot, you would bring those first fruits to the Temple -- not in your arms or in a sack but in a big basket that you wove for the occasion out of willow twigs. You'd probably arrange the fruit and vegetables beautifully, decoratively, in the basket, with an Alice Waters or Ariana Elster-like level of care. No animals, no meat. Your offerings are vegetarian and violence-free.

You'd approach the Temple with your basket of fruit.

You'd place the basket on your shoulder, or maybe on your head, making you look like a somewhat more modest Carmen Miranda, and you'd walk to the steps of the Temple, amidst crowds of people there for the same purpose, all wishing each other chag sameach - happy pilgrimage. Lutes and lyres would be playing and there would be dancing and talking and poetry. Or maybe it would be solemn and the procession would move in a hushed, dignified way, like Catholics awaiting communion.

When it was your turn, the priest on duty would greet you and you'd say, "Today I am affirming to Adonai, your God, that I have come to the land that Adonai promised to our ancestors."

The priest would take the basket from you and place it before the altar or maybe wave it in the altar's direction and place it elsewhere or maybe put it back in your hands for the moment.

And then would be your time to recite a memorized speech, in Hebrew, over which you undoubtedly would have butterflies because your Hebrew is probably rudimentary and this is an important moment. You would take a deep breath and recite words beginning with:

ארמי אבד אבי

Arami oved avi...

My father was a wandering Aramean...

You probably remember this speech from the Passover seder. It continues:

He went down to Egypt as an immigrant with just a small number of people; but there they became great and populous. The Egyptians were cruel to us, humiliating us and imposing harsh labor. We cried out to Adonai, the God of our ancestors, who heard our voice and saw our suffering... and brought us out of Egypt with a mighty hand... and brought us to this place, this land, flowing with milk and honey. And now I bring the first fruits of the land that Adonai gave me.

And that would complete your offering. These words constitute a statement of national history and identity, articulated as family history, and personal identity. My father was a homeless wanderer. Even those who had converted to Judaism said those words, because they were considered to be the spiritual descendants, even if not the genetic ones, of Abraham and Sarah. My father was a wanderer, and then we were slaves, and now we are free.

Missing are the 40 years of wandering in the desert and the receiving of Torah. Instead the focus of this ritual is redemption from despair and arrival at a new beginning. The sweep, the arc is from suffering to offering. I went from suffering to safety, you say to the priest, and here is my offering, here is my gratitude. Over and over, every year.

Suffering to offering.

Oy, what I went through you wouldn't believe. Here, have a piece fruit.

Suffering to offering. Gratitude made physical, made gastronomic. Even today, three thousand years later, we all know that nothing says thank you like a basket of fruit.

Now let me tell you about this week's haftarah. It is from the Book of Isaiah, set in the aftermath of the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem, and it begins:

קומי אורי כי בא אורך וכבוד ה' עליך זרח

Kumi ori ki va orech uch'vod Adonai alayich zarach.

Arise, shine, for your light has come. Adonai's glory is shining upon you. Darkness may cover the earth...but Adonai will shine on you. You will reflect Adonai's glory. Nations will be drawn to your light, and kings to the brightness of your radiance.

It is a haftarah of hope. It reads like a thesaurus entry; there are probably 8 Hebrew synonyms for the word light within the first three verses. When things seem bleak, Isaiah seems to say, there is not just a light at the end of the tunnel. There is light here, right now, bathing you. Bright, glowing. You just have to believe it; you just have to open your eyes and squint in the brightness.

So what is the lesson then for this time of year? How do these two moments of text reflect on our lived moment of self-examination, self-criticism, and atonement?

I propose a couple ways. One is prescriptive; one is descriptive. That is, one suggests a practice and the other its effect.

So here's the practice. In the discipline of teshuvah, "I'm sorry" cannot be the only mantra. It must somehow be paired with "thank you." Atonement and gratitude need to walk hand and hand. How can we do this?

We might look to feel grateful for the opportunity to become whole again each year. Or we might try to be grateful that we are walking this planet even while we are aware of our missteps. Or maybe we look inside and see we haven't at every moment been our best selves, but we are grateful that we have a best self, a clear image of who we might be that impels us to do better.1

Maybe the practice of gratitude has its best use in our teshuvah work with others. When you ask a loved one for mechilah, for forgiveness, maybe supplement with gratitude. I'm sorry if I've done anything to hurt you; and I'm so grateful to have you in my life. Or lead with gratitude: I'm so blessed that you're in my life; it makes me so sorry that I've hurt you.

This is useful. Because plain old apology has a tendency to hit the brakes on a relationship. It may be completely sincere and necessary and the apology accepted, but it can be followed by awkwardness and sometimes, alas, a hardening, a shell of self-protection against future hurt. But gratitude can soften that hardness. Gratitude can move us forward once again.

And don't stop at words of gratitude. Offer your first fruits, whatever those are. Your creativity. Your wit. Your love. Your help. Your care. Your shoulder. Offer something of the best of yourself to help pave the road ahead.

And that is, perhaps, why teshuvah is a kind of contraction. Not to make us feel small. But to make room for a new beginning, for our better selves. Teshuvah is not a shrinking but a kind of tzimtzum - a contraction that creates space, like God's first act of tzimtzum, making way for Creation, making way for the first words, yehi or - let there be light.

Your expansive teshuvah - atonement paired with gratitude, will make you radiant. Your expansive teshuvah will pull back the curtains and let the light in or let your light out. As Isaiah told us,

Kumi, ori, ki va orech.

Rise and shine because your light has arrived.

And so may we do our teshuvah differently this year. May we express our gratitude for each other and for our lives and for our best selves. May we offer our best to those around us. May we learn to say, "I'm so grateful for having you in my life; for having the chance to clear the air. I offer you my best. This is my teshuvah." And may that teshuvah let the light shine in all our lives.

And let us say, Amen.

(And then would it hurt to send a basket of fruit?)

1. I am grateful to Rabbi George Gittleman for this particular insight.

By the Waters: Yom Hashoah 2011

Invocation, Sonoma County Yom Hashoah Commemoration 2011

Good afternoon. Shalom aleichem.

It is again my great honor to offer an invocation for today's observance of Yom Hashoah. We gather today, as we do yearly, to tell and hear our stories. We do our best to honor this testimony by listening, taking in what we can, and finding some hook by which we can remember and share it.

Armed with cameras and computers, we can ensure that future students of the Holocaust and human history will be able to unlock and explore the individual experience of many survivors, and of the survivors' survivors as well.

And yet, as time inevitably wears away at memory, so much specificity will be lost. So much dear specificity has already been lost. But I believe that if our individual stories do give way, they will give way to a big story, a great collective story, as brushstrokes give way to the painting. It will be a story that begins with the Shoah, but doesn't quite end there. A story of loss, yes. But also of courage, resilience and renewal. This story is still being written.

["By the Waters of Babylon" by Evelyn de Morgan (1883)]

We do, though, have a model that can instruct us. Over 2500 years ago, Jerusalem was conquered and our Temple destroyed. The Jews who survived were deported to Babylon. It was a calamity beyond any our people had faced. The end of a kingdom, a way of life; the seeming end of a community.

We no longer know the individual suffering or bravery of any particular Jew of the time. But we know the big story, the epic sweep of this event and its aftermath. Because it's not just a story of loss but also of survival and renewal.

The Babylonian Exile set the stage for a new Jewish world in which we read Torah publicly. And in which we pray familiar prayers communally. And in which our thinking is guided by the law and lore of Talmud. The Destruction of the Temple remains a symbol of loss, but also of the grit and genius of our people.

And we remember the Temple of Jerusalem because the story, the big story, has come down to us with song and poetry and practice. Every year we mourn with familiar words. Eychah yashvah vadad ha'ir — "How lonely sits the city that was full of people," we recite from Lamentations, "how she has become like a widow." We honor the suffering of the bereft, displaced Jews. Al naharot Bavel — "By the waters of Babylon," we can still hear them sing in Psalm 137, "we sat down and wept, and we remembered Zion."

So now it is our turn. It is for us, and our students and our children and those who come after them, to write our big story. The story of our People — what we lost, how we mourned and, we pray, how we once again came to flourish. An enduring story of loss and renewal.

And so may we be blessed to write this story with such power and beauty that those who follow in 100 years — or 500 or 2500 — can hold this newest, greatest calamity in their hearts; that they can appreciate how it changed the face of Judaism in ways we can't at this moment even predict; and that they will know how in the aftermath we sat together by the waters of the Mediterranean or the Pacific; in Tel Aviv and Buenos Aires and Miami and Santa Rosa. And we wept. And we remembered.

Sing: Babylon

Much appreciation to Lorenzo Valensi, Anna Belle Kaufman and Alicia Cohen for lending their voices and musical skills to this invocation today.

Seder Tonight? Be a Stack of Matzah

The final matzah in the stack is Redemption - our belief that despite all our narrow places, our setbacks, and our hard-earned, self-protective cynicism, change is possible. Does this require a belief in divine intervention? Absolutely -- if we also believe that we are how the Divine acts in this world.

Read more